After providing lettering for a translated Norakuro story by Suiho Tagawa that appeared in Kramers Ergot 6, Sammy Harkham and Alvin asked me to put together a lecture to deliver at the Hammer Museum on the occasion of the book's release. Despite feeling that I wasn't really the person for the job, I accepted, figuring if I didn't do it likely no one else would. This lengthy post contains the slides as well as a few notes that I referred to during my speech. It should be noted that it contains some potentially disturbing images.

Thanks to Milton Knight for providing the animation clips and fellow Mome contributor Tom K. for providing contemporary photographs of the Norakuro Museum. Please bear in mind that I'm not a scholar, nor do I speak Japanese; I’m just the letterer! Bear with me. I first heard of Suiho Tagawa from Daniel Clowes, who had a multivolume set of his work that I saw during a visit. I also read Chris Ware list him as an influence in Comic Art magazine.

Who was Suiho Tagawa? Born 1889, died 1989. In his 40s, he created the series Norakuro about an orphan dog in the military service for Shonen Kurabu magazine. The series followed the dog through a series of military promotions. He begins as a private and rises in rank. Not much information is available in English. Described on the internet as an “anarchist.”

Since I don’t have biographical data, I want to say a little bit about the time period in Japan based on some rudimentary research and simply look at some slides of his work, since they are difficult to come across in this country.

But first let’s watch a two minute Norakuro cartoon. I should mention that these clips have a new dubbed soundtrack. I am not sure whether the original soundtrack, if there is one, still exists.

The time period during which Tagawa’s work appeared, 1931-1941, is the precursor to WWII and is sometimes referred to as "The Dark Valley." Japan was an imperialistic military state. There was widespread poverty, volatile coups attempted by military factions where cabinet members were killed, and ill-advised military aggressiveness. This quote I think explains it best: “In Japan, fascism was imposed from above by the military and the bureaucrats, aided by civilian rightists. It is not comparable to the mass parties of Germany and Italy, was not very effective in organizing or mobilizing the populace, and was not led by a charismatic leader.” This period is bookended by two events: in 1931, the Mukden Incident, and in 1941, the invasion of Pearl Harbor.

This slide serves as a geographic refresher course. The feeling of the time was one of “manifest destiny,” Japan standing in front guarding Asia. Note Mukden and Manchukuo on map. There's a line of dialogue in the Norakuro story in Kramers that states, “A new Asia can be created." Army Minister Sugiyama said, “We’ll send large forces, smash them in a hurry, and get the whole thing over with quickly.” The inability to conquer the vast China led to the conflict of WWII and eventual defeat.

This slide serves as a geographic refresher course. The feeling of the time was one of “manifest destiny,” Japan standing in front guarding Asia. Note Mukden and Manchukuo on map. There's a line of dialogue in the Norakuro story in Kramers that states, “A new Asia can be created." Army Minister Sugiyama said, “We’ll send large forces, smash them in a hurry, and get the whole thing over with quickly.” The inability to conquer the vast China led to the conflict of WWII and eventual defeat. Here we see the same map on a page from Norakuro.

Here we see the same map on a page from Norakuro. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn these are maps of specific battle areas in China. Is that the Yangtze River?

I wouldn’t be surprised to learn these are maps of specific battle areas in China. Is that the Yangtze River?

This comic page from the Tintin book The Blue Lotus by Herge is an illustration of the Mukden Incident of 1931. Officers in the Japanese army in Manchuria blew up a railway section and blamed it on the Chinese as a pretext for invasion. Herge also dramatized Japan leaving the League of Nations in 1933. Another lecture could compare the two cartoonists. Both have things in common--children’s comics, the clear line, and war compromise.

This comic page from the Tintin book The Blue Lotus by Herge is an illustration of the Mukden Incident of 1931. Officers in the Japanese army in Manchuria blew up a railway section and blamed it on the Chinese as a pretext for invasion. Herge also dramatized Japan leaving the League of Nations in 1933. Another lecture could compare the two cartoonists. Both have things in common--children’s comics, the clear line, and war compromise. During this period, the public was told to believe four things: 1. The emperor was the natural ruler of the world. (Does the man on the horse look like that to you?) 2. The Japanese were racially superior to the rest of the world. 3. It was the destiny of Japan to control Asia. 4. What was called the “Greater East Asian War” was a holy war.

During this period, the public was told to believe four things: 1. The emperor was the natural ruler of the world. (Does the man on the horse look like that to you?) 2. The Japanese were racially superior to the rest of the world. 3. It was the destiny of Japan to control Asia. 4. What was called the “Greater East Asian War” was a holy war. During this conflict there were also terrible atrocities such as the Rape of Nanking in 1937. 300,000 non-combantants were killed, and there was widespread brutality, looting, and arson. The caption reads, "The Japanese media avidly covered the army’s killing contests near Nanking. In one of the most notorious, two Japanese sublieutenants went on separate beheading sprees near Nanking to see who could kill one hundred men first. The Japan Advertiser ran their picture under the bold headline: 'Contest to Kill First 100 Chinese with Sword Extended When Both Fighters Exceed Mark—Mukai Scores 106 and Noda 105.'" This page is from a book about the Rape of Nanking; I’d say avoid the pictures section if you can.

During this conflict there were also terrible atrocities such as the Rape of Nanking in 1937. 300,000 non-combantants were killed, and there was widespread brutality, looting, and arson. The caption reads, "The Japanese media avidly covered the army’s killing contests near Nanking. In one of the most notorious, two Japanese sublieutenants went on separate beheading sprees near Nanking to see who could kill one hundred men first. The Japan Advertiser ran their picture under the bold headline: 'Contest to Kill First 100 Chinese with Sword Extended When Both Fighters Exceed Mark—Mukai Scores 106 and Noda 105.'" This page is from a book about the Rape of Nanking; I’d say avoid the pictures section if you can.

Remember to read right to left. One of the biggest objections to Norakuro is the depiction of the Chinese as pigs. The translator told me that the pigs’ dialogue is meant to be a stereotyped version of Chinese dialect. Japanese racism was apparently widespread. One book I read had a Japanese general telling a correspondent, “To be frank, your view of the Chinese is totally different from mine. You regard the Chinese as human beings while I regard the Chinese as pigs.” Not having read the translations of all of Tagawa’s comics, it’s hard to confront this topic. Note beheading.

Remember to read right to left. One of the biggest objections to Norakuro is the depiction of the Chinese as pigs. The translator told me that the pigs’ dialogue is meant to be a stereotyped version of Chinese dialect. Japanese racism was apparently widespread. One book I read had a Japanese general telling a correspondent, “To be frank, your view of the Chinese is totally different from mine. You regard the Chinese as human beings while I regard the Chinese as pigs.” Not having read the translations of all of Tagawa’s comics, it’s hard to confront this topic. Note beheading. From Ethan Persoff’s website of instructional and propaganda comics, an excerpt from "How to Spot a Jap." Drawn by Milton Caniff, an artist featured in the Hammer’s Masters of American Comics exhibit.

From Ethan Persoff’s website of instructional and propaganda comics, an excerpt from "How to Spot a Jap." Drawn by Milton Caniff, an artist featured in the Hammer’s Masters of American Comics exhibit. Typical WW II depiction of the Japanese in American comic books. Offensive, borderline camp. Giant Robot published a gallery of these covers in one of their issues. This cover shows when kinetic action shades into ideology.

Typical WW II depiction of the Japanese in American comic books. Offensive, borderline camp. Giant Robot published a gallery of these covers in one of their issues. This cover shows when kinetic action shades into ideology.

Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize winning Maus also uses an animal metaphor. Cats are Nazis, Mice are Jews, Pigs are Poles.

Wally Wood from Two Fisted Tales. Although Harvey Kurtzman's war comics were complex, this is more what people expect to see in a war comic. Sgt. Rock, Sgt. Fury, types, kinetic action.

Contemporary war comic by Shigeru Mizuki. Sent to Papua, New Guinea. Got malaria, watched his friends die, and in Allied air raid lost his arm. Taught himself to draw with his right hand. Worth his own lecture. Famous for children’s comic “Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro.”

Photograph of original art. Note wash and pasted in lettering.

Books follow from private higher. Early stories appear similar to the barracks humor of Sad Sack or Beetle Bailey.

From a Beetle Bailey comic.

War comics cloud into propaganda. Right-minded, boring. The last panel balloon on this page reads, "Please note that all human beings have exactly 27 bones in each hand! They are arranged the same no matter whether the man lives in Africa or America."

From The People’s Comic Book, Chinese propaganda comics published in the U.S. in the 70s. Very stiff.

Cartoonists in Japan may have been influenced by films as much as comics. Poster of Harold Lloyd, silent film comedian.

Photo of Tagawa. Note Harold Lloyd glasses.

Photo of Tagawa. Note Harold Lloyd glasses. This is, of course, Bambi, by, as we all know, Osamu Tezuka.

This is, of course, Bambi, by, as we all know, Osamu Tezuka. There is also a version he did of Pinocchio, but it seems unlikely either will be translated here.

There is also a version he did of Pinocchio, but it seems unlikely either will be translated here. But more than Disney, the obvious influence will be determined after this short video clip that dramatizes the pages above.

But more than Disney, the obvious influence will be determined after this short video clip that dramatizes the pages above. Yes, Felix the Cat, known for his brooding walk.

Yes, Felix the Cat, known for his brooding walk.

I used Felix the Cat's lettering as a guide when I lettered the translation.

I used Felix the Cat's lettering as a guide when I lettered the translation. I also tried to use similar punctuation. Well, there is almost no punctuation, usually one or two exclamation points.

I also tried to use similar punctuation. Well, there is almost no punctuation, usually one or two exclamation points. Tagawa is more streamlined. Now let's look at a five minute clip from General Norakuro (1934), again dramatizing the pages above.

Tagawa is more streamlined. Now let's look at a five minute clip from General Norakuro (1934), again dramatizing the pages above. Now the comics. This is a slipcase for one of the collected volumes.

Now the comics. This is a slipcase for one of the collected volumes. Page layouts are static, mostly 3 panels to a page, often usage of full page and double page. Symmetrical.

Page layouts are static, mostly 3 panels to a page, often usage of full page and double page. Symmetrical.

The top left circle is flip-book animation.

The top left circle is flip-book animation.

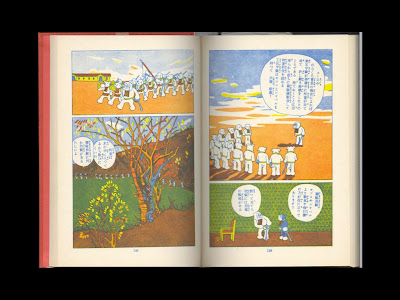

For war comics, Tagawa shows a special interest in depicting nature.

For war comics, Tagawa shows a special interest in depicting nature.

Note split panel action.

Note split panel action.

Beautiful Art Deco explosions.

Beautiful Art Deco explosions. Original art from Norakuro Museum, not sure of size. Note racist depiction of natives. Washes act as color guides?

Original art from Norakuro Museum, not sure of size. Note racist depiction of natives. Washes act as color guides? Printed version of same spread.

Printed version of same spread.

Tagawa also used double page spreads for long horizontal panels.

Striking use of silhouettes.

Now let's close the books and look at photographs of the Norakuro Museum in Japan.

This is the street where the Norakuro Museum is located in Tokyo, Japan. (These are all photos from fellow Mome-ster Tom K. Thanks, Tom!)

Tom said he was told that Norakuro was for "grandmothers." Kids were more interested in Gundam Wing.

Set of volumes scans are from in upper left. In the middle is most likely an issue of the manga in which the work was originally serialized.

Set of volumes scans are from in upper left. In the middle is most likely an issue of the manga in which the work was originally serialized. Postcards showing pastel work.

Postcards showing pastel work. Similar to the Charles Schulz Museum which also has drawing area preserved.

Similar to the Charles Schulz Museum which also has drawing area preserved.

Continuity of merchandise.

Continuity of merchandise.

From animated series, 1980s.

From animated series, 1980s.

Drawings by children. Closing remarks. My own feeling is we are currently living in a time of war, where our government seems to have imperial and business aims detached from the will of the common people. I think that makes this work resonate in the imagination.